|

|

|

|

|

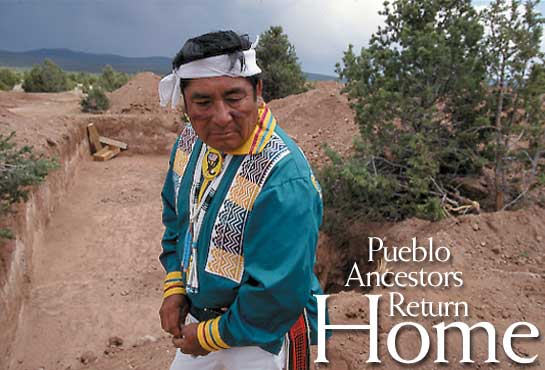

At the Jemez Pueblo Reburial

Step into the world of writers and photographers as they tell you about the best, worst, and quirkiest places and adventures they encountered in the field.

|

Get the facts behind the frame in this online-only gallery. Pick an image and see the photographer’s technical notes.

|

Click to ZOOM IN >>

Click to ZOOM IN >>

Click to ZOOM IN >>

Click to ZOOM IN >>

Map of Ceremonial route

Click to enlarge >>

|

|

By

Cliff Tarpy

Photographs by

Ira Block Photographs by

Ira Block

|

Ancient Native American remains are welcomed back to New Mexico after some 80 years away.

|

Get a taste of what awaits you in print from this compelling excerpt.

The violation of the graves was another sad chapter in the history of Pecos Pueblo, once a thriving village of 2,000 people living in multistory adobe structures. Situated near the river that shares its name, Pecos became an important trading center. Plains Indians brought flint, shells, and buffalo hides to exchange for the textiles, pottery, and turquoise of the Pueblo tribes. Pecos had grown rich and powerful by the time Spanish colonists arrived in 1598. Yet the newcomers’ rapid influence was underscored by their building an adobe mission in 1625. During the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, Pecos Indians killed the local priest and destroyed the mission’s church. The Spaniards returned to build another church, whose ruins survive at Pecos National Historical Park.

By the 1780s the population of Pecos had fallen to under 300 from raids by Comanche warriors, diseases contracted from Spaniards, and migration. In 1837 Pecos leaders told the governor in Santa Fe, then part of Mexico, of their intention to relocate to Jemez Pueblo. Other pueblos were closer, but Jemez had extended an invitation to the diminished tribe. The fewer than 30 remaining Pecos Indians gathered their belongings in 1838 for the 80-mile walk west to their new home.

Get the whole story in the pages of National Geographic Magazine.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Photographer Ira Block documents what’s been called the single largest repatriation of Native American ancestral remains. Listen to him describe the challenges of covering such a sacred and sensitive occasion.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| How much effort should museums make to return ancient remains and artifacts to cultural descendants? And who should initiate such actions? Tell us what you think. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| In More to Explore the National Geographic Magazine team shares some of their best sources and other information. Special thanks to the Research Division. |

|

|

|

|

Though it was an archaeologist who removed the human remains and artifacts at Pecos Pueblo, it was also an archaeologist who helped put them back. Alfred V. Kidder studied and excavated Pecos Pueblo from 1914 to 1929, sending artifacts to the Peabody Museum in Andover, Massachusetts, which sponsored the project, and human remains to the Peabody Museum at Harvard, where he had received his Ph.D. In 1991 William J. Whatley, the Jemez Pueblo tribal archaeologist, began searching for these remains and artifacts, with the intent of moving them to the Pueblo of Jemez, the legal and administrative representative of the Pueblo of Pecos by a 1936 act of Congress. Eight years later Whatley stood graveside as the only non-Indian to witness the reburial. Kidder, though, was there too: He is buried on a hillside not far away, close to where he once excavated.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

National Park Service

www.nps.gov/peco

Find Pecos National Historical Park information, including directions, best times to visit, and special programs.

Pueblo of Jemez Dept. of Resource Protection

www.nmia.com/~quasho

Learn more about the Pueblo of Jemez—its history, culture, and myths at Additional Pueblo information, a schedule of events, directions, and contact numbers can be found at the Pueblo’s Department of Tourism, at www.jemezpueblo.org.

National Park Service’s Guide to NAGPRA

www.cr.nps.gov/nagpra

Find out more about the (1990) Native American Graves and Repatriation Act and learn about current issues, get contact information, and find guidance on the process of repatriation.

Top

|

Kessell, John. Kiva, Cross, and Crown. National Park Service, U.S. Dept. of the Interior, 1979.

Kidder, Alfred. Pecos, New Mexico: Archaeological Notes. Robert S. Peabody Foundation for Archaeology, 1958.

Noble, D., ed. Pecos Ruins. Ancient City Press, 1993.

Sando, Joe. Nee Hemish. The University of New Mexico Press, 1982.

Top

|

Goble, Paul. The Legend of the White Buffalo Woman. National Geographic Books, 1998.

Walker, Paul Robert. Trail of the Wild West. National Geographic Books, 1997.

Roberts, David and Ira Block. “The Old Ones of the Southwest.” National Geographic, Apr. 1996, 86-109.

Newman, Cathy and Bruce Dale. “The Pecos—River of Hard-won Dreams.” National Geographic, Sept. 1993, 38-63.

Creamer, Winifred, Jonathon Haas, and Ira Block. “Pueblo: Search for the Ancient Ones.” National Geographic, Oct. 1991, 84-99.

Belknap, William, Jr. “20th-century Indians Preserve Customs of the Cliff Dwellers.” National Geographic, Feb. 1964, 196-211.

Sutherland, Mason and Justin Locke. “Adobe New Mexico.” National Geographic, Dec. 1949, 783-830.

Top

|

|

|

|

|